In 1942, four unsteady piano players responded to an ad placed by Bernard Gabriel, a concert pianist, publicizing a series of meetings to be held at his Manhattan apartment. Fear-racked musicians were invited "to play, to criticize, and be criticized, all to conquer the old bogey of stage fright."

Gabriel had no formal qualifications other than a confidence beyond his 30 years. Gabriel was, it was said, "non-timid" and he deployed rudimentary exposure therapy—insulting musicians and distracting them with loud noises—to inoculate them against performance anxiety. Soon Gabriel's "Society of Timid Souls" numbered more than 20, and copycat societies followed.

The world is not populated only by square-jawed heroes and sniveling cowards, as the Society of Timid Souls well understood. The vast majority of us find ourselves somewhere in the middle, wishing to be brave and yet easily frightened by what is frightening. Either that or we are capable of facing real danger one day, and the next being scared out of our wits by something comparatively trivial.

For stage performers and those with chronic illnesses, testing points may come virtually every day. For those who confront violence or natural disaster, the test may come once in a lifetime. Whatever the circumstance, when someone who appears small and ordinary is brave, it gives us all hope. It's this transformation, however momentary, from timid to brave soul that sits at the heart of how we measure ourselves as humans.

We exhort our children to be brave—about a nightmare, a first day at school. They are not striving to follow some blueprint of human virtue. They are just busy growing up. Learning to be brave in adult life—and not just among soldiers—could, should, and does have the same liberating effect upon grown-ups.

Buried Alive: The Overnight Saviors

"It's an earthquake," screamed Michael Runkel.

Ruth Millington, a British lawyer, and Runkel, a German photographer, were staying at Akbar's Guest House in Bam, Iran, over Christmas 2003.

The earthquake struck at 5:26 a.m. "I was in a deep sleep and woke up in a spinning, pitch-black washing machine. I couldn't see a thing. I stood up and felt the ground leaping up and down. Along with the noise of 20 locomotive trains thundering underneath the ground, there were the crashing metal roofs and smashing glass. I was thrown 15 feet across the room onto the other bed and suddenly the room came in on me. I felt bricks smash onto my head and I lay there thinking that if I didn't move I would die. I stuck my hand out and Michael pulled me up."

Once outside, Ruth ran forward with her hands in front of her and she felt a wall of rubble; she scrambled to the top. "Suddenly, the noise stopped. White dust hovered in the air and I remember saying, 'Where's the hotel?'"

Then the wailing began. "It was a low wailing, and it came from all around the city. It filled the air and it went on all day." Half of the population of Bam had been killed in two minutes. The majority of the survivors not only lost their families but were also injured, many seriously. The quake registered 6.3 on the Richter scale, not as high as some, but, owing to the fabric of the centuries-old mud-bricks, almost the entire old city had dissolved to fine earth and either crushed or suffocated people in their beds.

Where many would be immobilized, Millington—the faintly bossy, inquisitive, curly-haired lawyer—was galvanized. For the next nine hours, she and Runkel dug nine people out of the rubble with their bare hands and saved seven lives.

It began when Millington spotted a Belgian man bent over on the ground. "He was shouting, 'Natalie! Natalie!'" Millington saw just the crown of a head, hair and blood, and the rest of the body buried in rubble. "I could hear her suffocating. I froze for a couple of seconds and then I said, 'Get her out,' and I went over and knelt down. We were scrambling like dogs to get to her face."

It dawned on Millington that there were other people under the ground on which she crouched barefoot in her pajamas. So she asked the young man to carry on digging his girlfriend out, promising to return and check on them.

December 2003: Bam, Iran Earthquake! "I woke with Michael's hands around my ankles, dragging me off the bed, and his screams above a noise more deafening than any other I had ever heard."—Ruth Millington

With no sign of organized help, Millington and Michael divided the pile of rubble, each digging for survivors at either end. As the sun rose, the roads filled with cars and motorbikes carrying people looking for family and friends.

With daylight, they could truly get to work digging people out. The horrific images included two coughing heads sticking out of the rubble and tethered together by a metal bed frame; a young woman in a black hijab wailing and rocking back and forth holding a baby; a screaming German man, head down in the debris with only his feet sticking out; Millington was, in her words, "managing" locals enlisted to help her dig—as if she were managing ateam of junior lawyers on an acquisition. Millington worked through intuition. She would say, "There's someone underneath that, but where's the head going to be?" Then came the dust and the gravel and the matted hair. They used salvaged bedsheets to carry the injured down to the road; and everywhere there were bodies wrapped in blankets. Children and adults.

As the hours passed, Millington would liberate a head, scraping rubble from nostrils and mouths, and she promised the buried that she would not abandon them. She assured them that she would be back to continue digging, but first she had to be sure that no more people were drowning in the rubble. "It was like a business deal," says Millington. "I was calm and calculated, I knew I had to do X, Y, Z without emotion. Ironically, Michael and I have always been slightly competitive, which enabled us to be more successful. It may sound strange, but it's a quality that we used to enhance what we were doing."

They finished digging at three o'clock that afternoon, confident that they had accounted for everyone, alive or dead, in the hotel. After that, they had to get the injured to the hospital in Kerman, nearly 200 kilometers away. So Millington looted water while Runkel considered hot-wiring a car; eventually they harangued someone into driving his Jeep to Kerman. From there, everyone was transferred to Tehran, and ten days later, all were home.

"I never even felt like it was a choice," she says. "It was just something I did automatically. I know I was brave but you always think it's someone else who's brave; I just thought it was something that I had to do and if I was in that situation again, I would do the same. And if that is bravery then so be it, but I've never really quantified it as that." Is Millington troubled by the multitude she could not save? "I don't feel guilty about not being able to save the whole of Bam," she says with certainty. "You have to have a reality, and I worked to the best of my abilities with the limited amount of resources—one shovel and hands—and I saved these people's lives. I am proud of what we did."

Timid Soul: The Perennially Frightened Performer

"Many people would say that actors are just people who didn't get enough attention as children and that is why they need to dress up in other people's clothes and shout in the evening. And some of that is true," one veteran English actor explains. "I think we contribute something to society, but I would not wish to stand next to a fire-fighter or a disaster survivor and say we are brave."

In 1966, The Lancet published the findings of a study into the effect of beta-blockers on anxiety. This article was the first to suggest that the drugs, typically prescribed for heart conditions or hypertension, might also be used in the treatment of stage fright. Here was a pill that took away the debilitating physical symptoms of fear—nausea, dizziness, sweating, breathlessness, shaking. The beta-blocker of choice was Inderal. Some 20 years later, a survey by the International Conference of Symphony Orchestra Musicians revealed that 27 percent of its musicians had used this drug to mitigate stage fright. An upcoming study of 357 musicians across eight premier orchestras in Australia set the figure at nearly 30 percent.

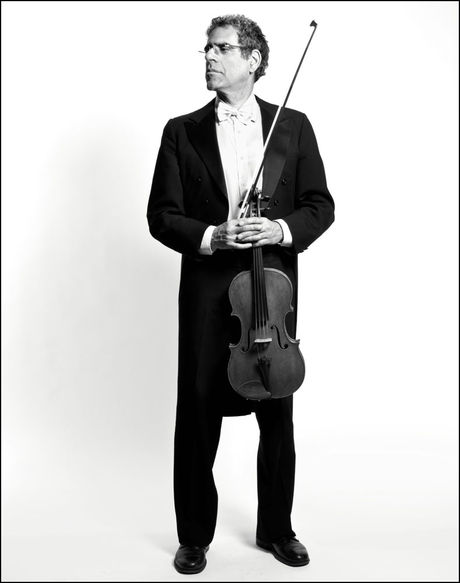

"I wish that I could have that sense of pleasure and enjoyment of playing in public without being medicated," says Ken Mirkin, a gentle, beetle- browed viola player with the New York Philharmonic. "I don't know why I have such panic over it," he adds. "I've spent years in psychotherapy and tried behavioral modifications—biofeedback, hypnosis, breathing exercises, yoga, visualization, everything—and the only thing that really helped was the Inderal."

Mirkin was 15 when he had his first experience of stage fright. Admitted to a prestigious summer music program, he entered a master class with a famous cellist. "I put the bow down on the string and it just bounced. I stopped and took a breath and started again. And it happened again. I started crying a little and everything was spinning, like I was going to pass out. I had never experienced anxiety like that before; and this set off a snowball effect. I was so afraid of it happening every time I played that it became a self-fulfilling thing. From that moment, I've had a lifelong battle with performance anxiety."

An Everyday Event: New York Philharmonic Rehearsals "You're putting your soul and your reputation on the line. Not only is it all of your skill and all the practice but it also has an emotional part, too."—Ken Mirken

Still in his teens, Mirkin started to take Valium for every audition, including the one that won him a place at the Juilliard School in New York. It starts with a sense of humiliation, followed by a fear of humiliation, followed by a fear of the fear. He felt that many spectators wanted to see him fail, like the circus audience that comes to see the tightrope walker fall.

His father was on Inderal for a heart condition, and a fellow student had mentioned its use for stage fright. As Juilliard graduation loomed, Mirkin was, in his words, "floundering." He took four of his father's pills to the Aspen Music Festival in Colorado that summer, and he did something he would never normally do: He entered the concerto competition. He took 10 milligrams of Inderal an hour before the performance. "For the first time since I was a child," he says, "I felt absolute calm. I started to play and my bow didn't bounce at all—and I won."

That autumn, 30 years ago, auditions for the San Francisco Symphony Orchestra and the New York Philharmonic followed. Ken took Inderal and was offered both jobs. Mirkin has been in the New York Philharmonic ever since, but he has never overcome his fear. Even after all these years, if a piece of repertoire is particularly challenging, he takes an Inderal. He expects to take it periodically all his working life. "I'm not sure I ever figured out what I'm afraid of," he says. "Maybe just a feeling that I'm not good enough. I don't think I ever had the confidence to think that I deserved to be something special." To him it's not counterbalanced by being in one of the best orchestras in the world. In fact, his fear may even be exacerbated by this.

Beta-blockers are a banned substance in the Olympics, where their use in archery or shooting would constitute cheating. And while it is clearly not "cheating" in a performance context, there is no getting away from the fact that this is Dutch courage of a sort. Most telling is that people who take Inderal tend to wish they did not. "I'd love to never take it again," says Mirkin. Some musicians equate it to taking Advil for migraines, and there is the rational fear of losing one's job, but a whiff of apology seemed to hang in the air that this dread-without-danger could not be conquered by willpower alone.

Nevertheless, the mechanisms of courage required to overcome stage fright are necessarily as real and true as the next sort. Mirkin says, "You're putting your soul and your reputation on the line every time you go out. Not only is it all of your skill and all the practice that you do but it also has an emotional part, too. So you're putting yourself in a vulnerable position when you perform. To me that takes a huge amount of bravery."

Confronting a Terrorist: The Off-Duty Firefighter

Angus Campbell is a veteran firefighter with the London Fire Brigade, but he is not talking about fighting a fire here. In the summer of 2005, on his way to work, Campbell defied thebystander effect—the diffusion of responsibility in the company of many bystanders. The off-duty firefighter confronted a suicide bomber who had just attempted to detonate a device on the London Underground. This was just two weeks after 52 London commuters had been killed in the July 7 suicide attacks.

Campbell got on the tube at Tooting Bec, toward the back of a carriage. "The tube traveled along, then there was a huge bang," he says. The explosion came from a young man wearing a rucksack that caught on fire. He was standing by the train door, opposite Campbell and next to a woman with a baby. Ramzi Mohammed, a Somali national, was known around the North Kensington Muslim community for his increasingly militant views. The backpack was filled with homemade explosives, although at this stage only the detonator had fired. Three similar explosions occurred that lunch hour on two other tube trains and a London bus, all part of a coordinated attempt to replicate the horror of two weeks earlier; although this time, all four devices failed.

"The smoke was white," says Campbell. "White is a clean smoke and I realized it was a bomb. I can remember the smoke and flames coming out of his rucksack and him screaming. He was obviously terrified as he was being burnt up the back of his neck." Mohammed threw the smoking rucksack to the corner, where it lay spewing bitter-smelling spongy stuff.

With the driver oblivious, the train rattled on toward Oval Station, a few minutes away. The carriage windows were open and the breeze from the tunnel cleared the smoke to reveal passengers running into the adjacent carriages. Within seconds, only Campbell, the woman and child, and the bomber remained. Campbell had started to run moments after the explosion, but the stroller was trapped next to a pole. Campbell went to the woman, tugged the stroller free, and they dragged it down the carriage when Campbell spotted the alarm lever, yanked it, and yelled into the speaker, "There's a bomb on the train. Help."

No answer.

Campbell now yelled up the carriage to Mohammed, "'What the f*ck is that? What on earth are you doing?' Then Ramzi Mohammed shrieked back at me, 'This is wrong. You are wrong. You are f*ck. You are wrong. You are f*ck.'"

July 2005: London Suicide Bombing "I can clearly remember the smoke and flames coming out of his rucksack and him screaming, screaming like you wouldn't believe. He thought he was meeting his maker."—Angus Campbell

Campbell pushed the woman and the stroller through the carriage door and he found himself alone with Mohammed. Where many might have just carried on through that door to relative safety, Campbell walked back toward the would-be bomber. "I didn't want to hurt him. I wanted to help the idiot." Campbell found himself in an almost comical situation with a man who was literally on fire. "He was clearly in pain."

Mohammed continued to flap his hands behind his burned neck and flailed his fists like a frustrated child. Campbell shouted again at the man: "'What have you done? You're trying to kill us. You tell me what that is.' I pointed at the rucksack."

A peal of laughter came from Mohammed, then he shouted back at Campbell, "No, this is f*cking bread. You are f*ck." Flour had been used to make the bomb.

Campbell still wanted to help him. "I can help you, but I want you to lie down before I come anywhere near you." But Mohammed would not lie down.

The train crawled into Oval Station and the driver came on the loudspeaker. "Whoever pulled the emergency cord, please make yourself known to me."

Campbell ran back to the microphone, "Don't open the doors. We've got him. Get the police." But the doors opened, and Mohammed bolted into the crowd and disappeared; the police caught him two days later.

"Everyone tells me I was brave. I didn't do very much. I rescued the woman and I rescued a child and I then went back and tried to deal with what was causing the problem. I acted responsibly. Was it brave? I don't know."

Some people have asked him why he didn't punch Mohammed. But Campbell, who wanted to help him, believes that would have been wrong. "And I probably would have lost," he says. "The adrenaline in his body was immense. When he ran, there were a lot of people on that platform and he mowed through them like they were grass. Imagine what he felt, imagine the fear!"

The fact that Campbell might have been blown to bits seems less affecting than the imagined thought processes of the man who would have done it, a man with whom Campbell alone had shared this bizarre, intense moment. "Ramzi Mohammed was tried for attempted mass murder—quite rightly—because that's what he tried to do," Campbell says. "The judge sent him down for 40 years. I dwell on it a lot. He was very young, and it's such a waste. I worry about him. He's only a child, a confused kid." Campbell was later awarded the Queen's Gallantry Medal.

Dying on the Outside: The Paralyzed Programmer

A man goes in to see his doctor, and after some tests, the doctor says, "I'm sorry, but you have a fatal disease."

"That's terrible!" says the man. "How long have I got?"

"Ten," says the doctor.

"Ten? What kind of answer is that? Ten months? Ten years? Ten what?"

The doctor looks at his watch. "Nine."

This is the joke computer scientist Hal Finney used to open a 2009 entry on an academic community blog, in which he revealed that he had been diagnosed with a fatal disease. To those who know him, this was very Hal—low-key, droll, to the point; but the diagnosis itself was no joke. Indeed it is hard to think of a worse one. Hal Finney was told he had a degenerative motor-neuron disorder called ALS, or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and the fact that it is fatal is just one final, devastating ornament to what it does to you first.

Sometimes known as Lou Gehrig's disease, after the famous New York Yankees player, ALS causes nerve damage, rapidly progressive muscle atrophy, paralysis, and ultimately respiratory failure. The disease takes from its sufferers with alarming speed the ability to walk, talk, move, eat, and eventually even to breathe. Most die within two to three years. In the meantime, ALS does not affect the higher brain functions—the ability to think, reason, and experience emotion—and there is little pain. The condition is often compared to being "buried alive." A nurse at St. Christopher's Hospice in London has said that ALS is the worst thing to get and that ALS patients may be the very bravest of all.

Hal had studied computer science at Caltech in the mid-1970s, and during his freshman year he met Fran, tiny, dark and pretty, with an oceanic smile. They had married straight after graduation in 1979, had two kids, and moved to Santa Barbara. Life was good. As Hal's career as a programmer progressed, he got into cryptography and wrote much of the code for the groundbreaking open-source software known as Pretty Good Privacy. When PGP became a major company, Hal had a great job there. He was, it seemed, at his height.

He was also a runner with a techno-geek's training program, using graph analysis about speed, distance, and so on. But in early 2009, almost overnight, his graphs went weird, the rate of improvement suddenly falling away. At first the doctor said that such a lull was part of aging; he was 53 years old. But by March, his speech had become slurred, so he returned to the doctor and the tests began. A definitive diagnosis of ALS came back.

There are luckier unlucky folk, those for whom the disease progresses more "indolently." Hoping he would be among them, in September 2009, Hal and Fran ran a half marathon, if only to make the point that they could. In a photo of the two of them crossing the finish line, they are beaming, sweaty, and pink-cheeked, their heads thrown back in relief, and they're holding hands, raised up in triumph. "But it wasn't a triumph," says Fran. "For Hal, a half marathon used to be nothing, but this one took a lot out of him. That was the last long run he ever went on in his life. So I'm in the photo, saying, 'Yeah! We did it!' and there's Hal saying, 'Oh this is so hard. I can't believe how hard this is.'" During the evening after the race, Hal's muscles seized up and he couldn't move.

September 2009: Half Marathon, ALS Diagnosis "I never recovered from this race. I miss running; it was a sudden and unexpected loss. Once I was no longer able to run, I viewed it as a chapter in my life that was over."—Hal Finney

It was a week until he was able to walk again. He could no longer run, and he viewed it as the end of a chapter in his life. Hal likens it to living in a really nice area and then you have to move away. You regret it, but then you go on to find ways to enjoy your life in your new circumstances. So running gave way to walking, and then walking with sticks, and then to a wheelchair, later a motorized power wheelchair. He does not go out much now.

A month after the 2009 race, Hal Finney wrote his blog entry called "Dying Outside," and this was what now began to happen to Hal with pitiless speed: "Even as my body is dying outside, I will remain alive inside," he wrote. This was both a threat and a promise, for here on his blog post, Hal Finney swore, in the clearest of terms, to do what 90 percent of ALS sufferers do not do: that is, to choose to live. In practical terms, this meant that before respiratory failure was imminent, Hal would opt by prior arrangement for tracheostomy and mechanical respiration to stay alive. This way, survival with ALS becomes a long-term possibility, as evidenced by Stephen Hawking and others.

Hal also wrote in the blog entry: "ALS takes away your body, but it does not take away your mind, and if you are determined and fortunate, it does not have to take away your life... I hope that when the time comes, I will choose life... I may even be able to write code... even from an immobile body. That will be a life very much worth living."

By the time I first spoke to him, in March 2011, Hal was just able to speak, a series of muffled grunts and groans, but Fran would stand behind him. Half-leaning on his shoulders, half-hugging him, she would "translate." But his eyes danced with warmth, energy, and animation. It's as though he was peeking—impishly and entirely against the rules—over a high wall designed and built to shut him out, but thankfully not quite able to do so.

A month later, he had an elective tracheostomy. With the upside of long-term survival came the downsides—no speaking, no eating, unholy discomfort. Anything Hal wants to say, he types onto the screen of an iPad with a short, black, prodding stick, clutched uncomfortably in a crumpled hand.

"Right after surgery," writes Hal, letter by letter, "I questioned if dying wouldn't have been much simpler." Then he pushes a button, and an automaton voice reads the sentence. "I didn't realize I would lose speech so completely, and it's more frustrating than fearful."

"When I learned that Hal had ALS, I was so panicked, and Hal's reaction was, 'Don't worry, we have time.'" Fran laughs. "We haven't had as much time as I was hoping. Still, I can't think about the long term because it does scare me, so I'll let Hal give me the courage that he has."

One realizes just how symbiotic their two forms of bravery are. This is a kind of collective courage in miniature, built around this marriage in which each's mettle would be impossible without the other's—Fran fighting, Hal adapting, Fran caring, Hal enduring. "I hope for two or three more years," he writes. "Any more will be a bonus." He doesn't show the merest whiff of anger or sense of injustice. "And I don't really view myself as brave. I'm just surviving. Survival takes all my energy."

No comments:

Post a Comment