A SUCCESS editor trains with the man who tackled one of the most improbable athletic feats in history, completing 50 Ironman races in 50 days.

Ready?” He asks with a grin as he sets up some weights.

I nervously nod and force a half-smile.

We step out of his garage onto his driveway to start the day’s workout. And after a simple warmup of a few lunges, squat jumps and other exercises, I’m already winded. He can tell because he asks whether I need a drink of water. I need it, but I’m too proud to say yes. For some frivolous reason, I feel as if drinking water right now is a sign of weakness, and I don’t want to seem weak in front of a guy who is possibly the most physically enduring man alive.

Six weeks before our workout, he accomplished perhaps the greatest display of physical endurance in history: He completed 50 Ironman races in 50 consecutive days. In 50 states. An Ironman is a 2.4-mile swim, a 112-mile bike ride and a 26.2-mile marathon. Simply finishing a marathon is challenging enough. If you’ve never competed in one, you’re in for months of devoted training as you work up to perhaps four, five or more hours of exhausting running. Now imagine adding a six-hour bike ride on top of that and then continuously swimming for another hour and a half. (These times assume you’re a very well-conditioned athlete.) But he didn’t just do this once; he did it 50 times on 50 consecutive days while traveling across the country.

When I think about all of that, I’m embarrassed that I’m already panting after our warmup, but I shouldn’t be. Despite what he has accomplished, he doesn’t act like he’s better than I am or judge me for being out of shape. He’s just James Lawrence, 39, husband and father of five from Orem, Utah, south of Salt Lake City.

We step inside his garage to begin the weights portion of our workout. His garage looks like yours probably does: a little messy with random tools and old things hanging everywhere on the walls—except he doesn’t park his car in here. In the middle of his garage is a workout pad surrounded by sets of weights and other equipment such as his stationary bike. This isn’t where you would expect an athlete of his caliber to train for Ironman races, and he likes it that way. He says he takes pride in not being rich. He lives in a normal-sized home on a cul-de-sac in a typical middle-class American neighborhood.

Lawrence wasn’t always a world-class endurance athlete. And he has no particular natural gift for endurance racing. A native of Canada, Lawrence wrestled in high school, and he was pretty good at it—ranking fourth nationally at one point. But he didn’t even run in his first race until he was 28, when his wife, Sunny, signed him up for a 4-mile fun run. He failed miserably then.

“I didn’t have a great experience, being passed by women pushing their kids in strollers,” Lawrence says. “My wife said I was pathetic, signed me up for a marathon that was five months later, the Salt Lake City Marathon, and basically just said figure it out.”

He didn’t really figure it out.

“Again, I had a horrible experience. I didn’t want to allow being beaten down by a marathon to define me as an athlete.”

He didn’t. Lawrence decided to start doing some research on endurance competitions and began training for sprint marathons with a friend. But he took things slowly; he didn’t compete in a triathlon until four years later, finishing the 2008 Vineman Triathlon in Sonoma County, Calif., in 11 hours and 10 minutes.

And that’s how it started.

In 2010 Lawrence broke the world record for completing the most half-Ironman races in one year. He ran 22 of them in 30 days. But he wasn’t satisfied, so two years later he broke the world record for finishing the most full Ironman races in one year. He ran 30 races in 11 countries, beating the previous record of 20 races in one year.

Again, Lawrence wasn’t content. He wanted to push his mind and body to new limits. He asked himself what was the craziest thing he could come up with, and he devised the 50-50-50 Project: 50 Ironman races on 50 consecutive days in 50 states.

That’s why I’m nervous about this workout. I’m here to push myself, but I’m not sure just how far this man who knows no mental and physical limits will push me. This is a man whose muscles and body became so toned and defined after his 50 Ironman races that he says he now suffers from body dysmorphic disorder—anxiety about his body appearance because his muscles don’t look the way they did at the peak of his 50 days. (After our interview, the photographers and I asked him whether he would let us photograph him with his shirt off to show his abs, and he adamantly said no.) I have no idea what kind of workout to expect from a guy like this. I told Lawrence what my exercise habits are like—I play soccer and run a couple of miles a few nights a week, but I also haven’t lifted a single weight in over a year.

"I’m here to push myself. Going into this, I have one goal in mind: Don’t stop."

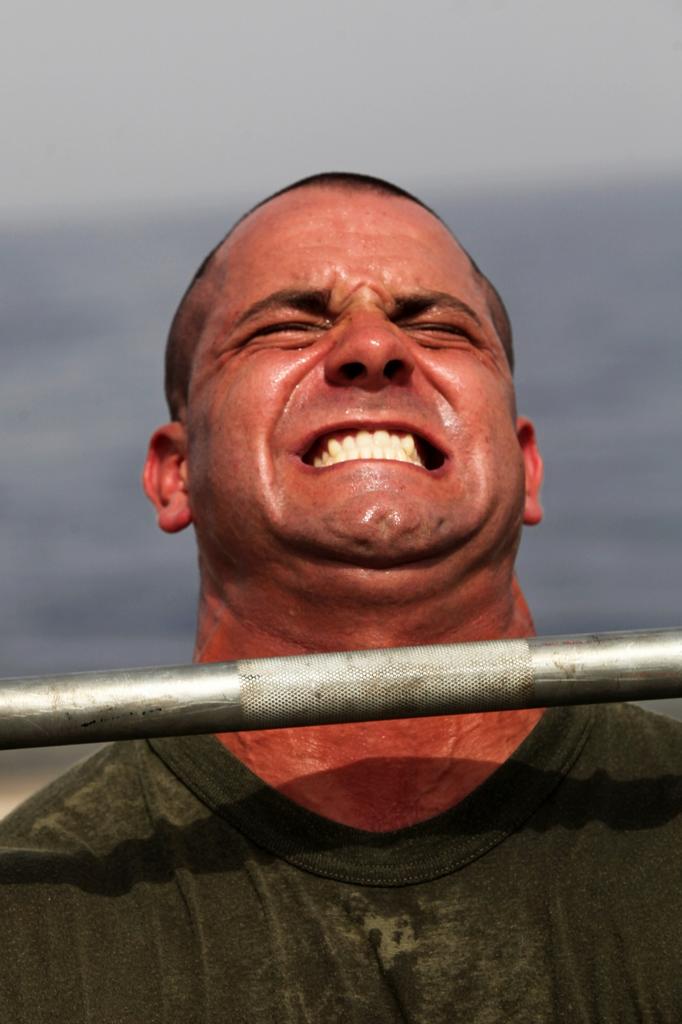

He hands me weights that are a few pounds more than what I think I can handle, but I don’t ask for something lighter. I’m here to push myself. Going into this, I have one goal in mind: Don’t stop. So as I struggle to lift a kettlebell over my head, I remind myself of that. And when I lose my balance doing a one-legged squat and feel my hamstring twinge, I remind myself of that again.

The first part of our workout consists of lifting weights and medicine balls, more lunges, pushups, hopping on plyometric jump boxes, and holding a one-minute plank that seems like an eternity. The workout is fast-paced, but both the pace and the weights are manageable. I take pride in finishing the first part of our workout, although my sense of achievement quickly fades when he tells me that this workout was more of a warmup for him when he was training for The 50.

Simply planning the logistics of 50 races in 50 states was no easy feat. Lawrence says he spent almost an entire year mapping all of the routes for his swims, bikes and runs. He had people on the ground in all 50 states who volunteered to help plan. “It was literally like running a small business,” he says. He was his own marketer, travel agent, accountant, manager, everything.

But Lawrence knew he couldn’t do it alone. He asked Dallas Makin, a sports chiropractor and owner of Utah Spine and Sport, to help with his recovery and injury prevention. Natalie Rasmussen came on as Lawrence’s massage therapist, and his friend David Warden coached him. “Many individuals have miscalculated James, but perhaps none so much as me,” Warden wrote in a blog post following the completion of Lawrence’s mission. “To be James’s coach was one of the greatest gifts I’ve received, a huge personal and professional boon that I now feel unworthy of.”

Warden wasn’t the only one who doubted this goal. Lawrence’s parents told him he was crazy. Friends told him it was impossible. But none of that stopped him. Lawrence was convinced he would accomplish his goal, and he had a lot of reasons to do so. His top five reasons were his kids: his daughters, Lucy, Lily, Daisy and Dolly, and his son, Quinn.

“I told them what the goal was,” Lawrence says. “The personal purpose of this was to find my mental and physical limits, but it was also to set the ultimate example for my kids.”

After months of training and planning, Lawrence began his 50-50-50 challenge in Kauai, Hawaii, on June 6. He then flew to Anchorage, Alaska, and on to the Lower 48, where he traveled by motorhome until wrapping up the adventure on July 25, back in Utah. (Amazingly he posted the best finishing time of the entire trip that day, needing only 12 hours, 46 minutes and 42 seconds to complete his final Ironman.)

“I had the mindset going into it that I was going to have to be in a hospital [to stop],” Lawrence says. “Obviously I’m smart enough with five kids that I was never going to risk exiting this life, but it was going to take a serious injury for me to stop moving. There was never a moment when I was like, ‘I’m quitting.’ It wasn’t an option; it wasn’t even a consideration. When you’re trying to accomplish something of this enormity you have to have that mindset."

"There was never a moment when I was like, ‘I’m quitting.’ It wasn’t an option; it wasn’t even a consideration. When you’re trying to accomplish something of this enormity, you have to have that mindset.”

For part two of our workout, we drive up to the Bonneville Shoreline Trail in the Wasatch Mountain Range—fairly close to Lawrence’s home. He tells me he often ran on this trail when he was training for The 50. I’m anxious again because I don’t know what to expect, and I’m also concerned about my hamstring after those one-legged squats. Lawrence is anxious, too. He’s biked and done some light workouts since finishing his challenge on Day 50, but he hasn’t done any running whatsoever. He’s not sure how his body is going to respond or how his knees and ankles are going to fare.

As we begin our uphill run, light rain begins to fall, and the wind hits our faces. After a few minutes of running, I can feel the elevation start to get to me. We’re up 5,500 feet—about 5,000 feet more than I’m accustomed to back home in Dallas. He likes to talk while we run, but I mainly just listen. I’m just trying to focus on my breathing and keeping up with him. Even though he hasn’t run once in the last six weeks, he takes on the inclines of the trail like they’re nothing. For me, the hills take a toll. With each step, I can feel the muscles in my legs and thighs exert themselves more than they possibly ever have.

The rain picks up, and the soil quickly becomes soggy. I can’t figure out how much of the moisture on my face is rain and how much is sweat. Now I’m not just focused on keeping up with Lawrence and breathing, I’m also focused on where I’m stepping. The last thing I want is to get hurt, or worse, fall on my face in the mud with photographers around. Though, as we continue running, I realize all of these things—the inclines, the rain, the soggy ground, the wind, the elevation—are excuses to not finish.

Lawrence had a lot more excuses that he could have used during The 50. He injured his shoulder during his fifth race, in Santa Cruz, Calif., forcing him to complete the next several swims with one arm while his shoulder healed. On Day 18 in Chattanooga, Tenn., his exhaustion caught up to him in the 30th mile of the bike portion. He fell asleep and fell off of his bike while riding, although luckily, he only suffered road rash. He lost some toenails during the adventure. He suffered a hiatal hernia. He pushed his body so hard that his heart had to focus on pumping blood to his major organs, causing him to lose feeling in his extremities. Six weeks after finishing The 50, he still experienced numbness in some of his fingers and toes.

And to top everything off, he averaged only 4½ hours of sleep per night, even struggling to get that, considering the discomfort of life on the road.

But Lawrence refused to let any of that stop him.

Quitting was even less of an option for Lawrence because he was surrounded by so much support. His family traveled with him through all 50 states. His eldest daughter, Lucy, ran a 5K with him in each state. But the support didn’t just come from his family; it came from strangers, too. Hundreds of people turned out to run, bike and swim with him or simply cheer him on.

“It was this awesome game of pingpong where I was inspiring people to come out, and because they were coming out, I was being inspired to continue to move,” Lawrence says.

The most motivation came from Dell Finney, whom Lawrence met on Day 39, in Benton Harbor, Mich. Finney weighs 326 pounds—down from 390 pounds at his heaviest. After running cross-country and track in high school to earn a college scholarship, Finney blew out his knee and lost a nerve in his right leg. Despite being told by doctors he would never be able to run competitively, he eventually worked his way back to running in 5Ks and later full marathons. Finney failed to complete the Wisconsin Ironman in 2014. He tried again in the 2015 and missed the bike cutoff by 73 seconds. When Finney heard what Lawrence was attempting, he came out to support him and run the last 5 kilometers of the marathon portion.

“I sprinted—we will call it a sprint—up to the front where [Lawrence] was, and I said, ‘I won’t be able to keep up with you for long, but I wanted to tell you my story and how you are an inspiration,’” Finney says. “After listening to my story, he told me that he wanted me to email him, he was rooting for me, and on race day he would be tracking me—which filled my heart with hope to the point of bursting. I half-expected to never hear from him again. Why would he care about just another overweight guy? I emailed him, and you know what? He emailed me back. It all started there.”

With the training help and encouragement of Lawrence, Finney will attempt the 2016 Wisconsin Ironman again in September. Lawrence guarantees Finney’s third attempt will be successful.

“He embodies [the idea] that no goal is too big, no dream is too big, and to never, never give up,” Lawrence says of Finney. “Nothing is impossible. His ‘impossible’ is one Ironman. Everybody is on a different journey in their lives, and for him that’s it.”

Lawrence’s “impossible” was to complete 50 Ironman races in 50 days. Finney’s is to complete one Ironman. Today my “impossible” is to complete a single workout with the Iron Cowboy, as fans have affectionately dubbed Lawrence. While our goals differ in size, our common denominator is our determination to achieve our objectives.

“The thing with The 50 was that there was only one person who needed to believe in me and that was myself,” Lawrence says. “To whoever is trying to accomplish their next big goal, I would say the biggest thing is to have over 100 percent conviction in what they’re doing.”

***

To finish this workout, I need to follow two of Lawrence’s examples: First, I need to stop thinking about the excuses I can use to quit. And second, I need to believe that I can. I think to myself, If he could complete 50 Ironmans in 50 days, I can complete this one workout.

Lawrence says the scenic views of Utah’s mountain ranges make the place a playground for endurance athletes. He’s right. As our run continues, we round a bend on the trail that reveals a gorgeous view of the valley below. He points out Brigham Young University and Utah Lake west of it. We pass sagebrush and other plants, but I keep looking at the aspen trees on Cascade Mountain in the range adjacent to us. He tells me the leaves of those trees will change colors in a few weeks, and the mountain range will glow in different shades of red, orange and yellow. I’m so taken by the scenery that for a while I forget I’m even running.

I ask Lawrence what he thought about while he was on The 50. He says sometimes he would have long conversations with himself, but most of the time, it was about focusing on what he would do in the next minute. Lawrence says he tried not to think about how many miles or days he had left; he just wanted to be perfect at whatever he was doing—running, biking or swimming—for the next minute.

For the rest of our run, focus is my focus. I focus on where I’m stepping. I focus on breathing right. I focus on keeping up and taking in the beautiful terrain—not on things like what I’m having for lunch or what time my flight leaves. I just want to focus on what I’m doing in that moment.

And before I know it, I’m done. The workout is over. I have accomplished my “impossible.” There aren’t 3,500 people here to celebrate with me—like those who came to see Lawrence on Day 50 but I did it. It was challenging, and while I know completing this workout is nothing compared to what Lawrence did, I still feel satisfied.

“I knew aside from being hit by a semi-truck [on Day 50], I was going to accomplish my goal,” Lawrence says. “I exceeded mine and everybody’s expectations. To have pulled it off and accomplished it, for myself and as a team, it was an incredible feeling of satisfaction.”

Walking back to the truck to head down the trail, I realize I’m still not exactly sure how Lawrence’s feat was humanly possible. Conviction, support, focus. What else?

“Patience and consistency,” Lawrence says. “You have to do a lot of little things right over an extended period of time. You have to focus on the basics, and you have to be perfect at them. That’s ultimately why I succeeded: I was perfect with the basics, and I had patience. I became an expert at a lot of little things, and that’s how I became successful—that’s one of the keys to success if anybody wants to tackle something of this enormity.”

“The size of the goal doesn’t matter. What matters is having the desire to improve yourself, push yourself to new limits and adopt the right mindset to make it happen.”

After leaving Utah, I felt sore for three days but also inspired. If a 39-year-old dad who didn’t run more than 4 miles until he was 28 could complete a goal of this magnitude, then 24-year-old me could at least get into better shape.

Since our workout, I joined a gym and started exercising six times a week. I decided my next “impossible” will be to run a 10K. My next goal still doesn’t compare to what Lawrence achieved or what Finney is training for, but if I learned anything from meeting and training with Lawrence, it’s that the size of the goal doesn’t matter.

What matters is having the desire to improve yourself, push yourself to new limits and adopt the right mindset to make it happen.

No comments:

Post a Comment